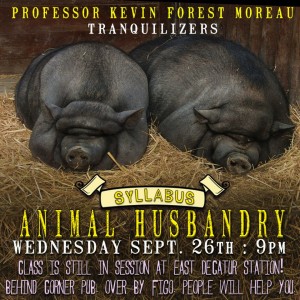

Editor’s Note: The following text is a lecture on tranquilizers written and performed for Syllabus: Animal Husbandry on Wednesday, Sept. 26. Syllabus is an offshoot of Write Club Atlanta in which six guest “professors” each present a seven-minute “class” on an assigned topic relating to that month’s major, which is chosen by the winner of the previous month’s event. (This month’s professors had the mischievous mind of Jackson Pearce to thank for Animal Husbandry.)

Good evening, class. I’ve been asked to address you tonight on the subject of tranquilizers, especially as they apply to the practice of animal husbandry. As it happens, my family history makes me uniquely qualified to speak on this topic.

Many of you are no doubt familiar with the work of my great-great-grandfather Alphonse Moreau—as immortalized by H.G. Wells in his 1896 novel The Island of Dr. Moreau, a loosely fictionalized account of my ancestor’s horrific experiments.

Alphonse was a renowned physiologist consumed with the idea of transcending his own animal nature to become the perfect human. Toward that end, he performed experimental surgery on wild animals, creating a society of beast-men struggling to shed their bestial ways.

Alphonse was a renowned physiologist consumed with the idea of transcending his own animal nature to become the perfect human. Toward that end, he performed experimental surgery on wild animals, creating a society of beast-men struggling to shed their bestial ways.

My Uncle Lafayette Moreau was obsessed with my great-great-grandfather’s work, and decided to follow in his footsteps. But lacking the resources and scientific know-how required to conduct genetic experiments, he was at something of a loss as to how to proceed.

And then, in 1987, he had an epiphany.

For those of you too young to remember, 1987 was the year Def Leppard released their multi-platinum album Hysteria.

Specifically, I’d like to draw your attention to the second single from that album, “Animal,” which contains this chorus:

“I got-ta feel it in my blood, whoa oh

“I got-ta feel it in my blood, whoa oh

I need your touch don’t need your love, whoa oh

And I want

And I need

And I lust.

Animal.”

In those timeless words, my uncle found his life’s calling.

I read to you now from his research journal:

“It is not our animal natures that inhibit us from greatness, but rather our human selves. The ideal state is not to be found in the banishment of our baser instincts, but by embracing them. And the only way to achieve that Nirvana, it is now clear, lies in the psychic and physical communion of man and beast.”

And so my uncle became a docent at Zoo Atlanta, to gain access to his subjects, and also became a self-taught expert on the subject of animal tranquilizers.

The use of tranquilizers in the breeding and mating of animals is not new. They’ve been used to reduce stress, and to prevent aggressive behaviors. But there’s no record of them being used to make animals open to sexual overtures—especially from a pasty human with male pattern baldness and an ill-considered RATT tattoo scrawled across his chest.

My uncle tried everything.

- Anxiolytics, or anti-anxiety agents.

- Neuroleptics, also known as antipsychotics—the hard stuff.

- Telazol, used to tranquilize large mammals such as bison and polar bears.

- Ketamine, also known as Special K on the streets.

But Uncle Lafayette was not a licensed medical professional. And so he found himself, in no particular order, mauled, mangled, impaled, clawed, gouged, gored and, in one particularly gruesome and overly detailed account, sexually assaulted.

By an ocelot.

It was after this last incident that my uncle stumbled upon the answer to his dilemma. Laid up on the couch, shot full of black-market phenobarbital, with all six seasons of The Nanny streaming on Netflix and a bag of Cheetos in his lap, he drifted in and out of consciousness for days, until he experienced what felt like an unbelievably sloppy but touchingly affectionate blowjob. He awoke to find his beloved Chocolate lab, Pudding, lapping up the fine orange Cheeto powder off of his crotch.

The solution had been under his nose the while time. If he was going to become one with an animal, what better candidate than man’s best friend?

Unfortunately, dear old Pudding proved no more receptive to his sexual advances than had the population of Zoo Atlanta. My uncle tried a variety of drugs—selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors, beta-blockers, Dramamine … even Ibuprofen. But, as he wrote, “While these have had a marked effect on Pudding’s general temperament, they do nothing to lessen her anxiety when I attempt to mount her.”

Two days after that journal entry, Pudding dug a hole under the fence and escaped, never to be seen again. Uncle Lafayette gave up his research soon afterward, and within six months died of internal injuries sustained during the aforementioned ocelot assault.

I thought that would be the end of these sordid experiments. But like my uncle before me, I’d become hooked—transfixed. I was convinced that his goal was not only worthwhile, but imminently attainable. After all, if the point was to free oneself from the burdens of human thought, then that by extension meant that the ideal partner would be one who was freed from consciousness—and, preferably, control over his or her motor functions.

You can find a number of suitable depressants in any bar in Atlanta: not just alcohol, but cannabis, Codeine, Oxycontin, Barbiturates, muscle relaxants, even antihistamines. But I would need something more assured of success.

The Rohypnol was surprisingly easy to obtain.

I walked into the Corner Pub that night, selected an attractive female, and engaged her in conversation.

But months of deep immersion in my uncle’s journals had left me so scarred, filled with images of ocelot-on-man action, that by now I was mainlining whatever I could get my hands on:

Cymbalta. Klonopin. Ativan. Paxil. Serax. Luvox. If there was a drug named after a character or a planet from Star Trek: The Next Generation or Farscape, I was taking it.

Cymbalta. Klonopin. Ativan. Paxil. Serax. Luvox. If there was a drug named after a character or a planet from Star Trek: The Next Generation or Farscape, I was taking it.

As a result, my hands were shakier than an NFL replacement referee’s judgment as I attempted to drop the tablets into my intended target’s drink.

You can probably guess what happened next.

I awoke in a jail cell, where for the next several weeks I engaged in sex that was neither dependent on tranquilizers nor altogether voluntary on my part, with an inmate who appointed himself my husband.

I don’t know his name, but the other inmates called him Animal.

Class dismissed.

b47c84